Antidepressant Monitoring Checklist

Symptom Monitoring Checklist

Use this checklist to monitor your teen's behavior and mood during the first 6 weeks of antidepressant treatment. Early detection of changes can help ensure safety and adjust treatment as needed.

Select symptoms to see what this means and what to do next.

Immediate Action Required

If you've checked "Suicidal thoughts or talk" or if symptoms are severe:

- Call 911 or your local emergency services immediately

- Take your teen to the nearest emergency room

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988

This is not a substitute for professional medical care. Do not delay seeking help.

When a teenager is struggling with depression, the decision to start an antidepressant isn’t just about picking a pill. It’s about weighing a real, documented risk against the very real danger of doing nothing. The black box warning on antidepressants for teens is one of the most talked-about, misunderstood, and debated safety alerts in modern psychiatry. It’s not a scare tactic-it’s a formal FDA alert, printed in bold black borders on every prescription label, telling doctors and families: These drugs may increase suicidal thoughts in young people during the first few months of treatment. But what does that actually mean in real life? And has the warning done more harm than good?

What the Black Box Warning Actually Says

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added the black box warning to all antidepressant labels in October 2004. It was based on a review of 24 clinical trials involving over 4,400 children and teens with depression, OCD, and other mental health conditions. The data showed that among those taking antidepressants, about 4% experienced new or worsening suicidal thoughts or behaviors. In the placebo group, that number was 2%. That’s a doubling of relative risk. No one died in these trials. But the pattern was consistent across multiple drugs-fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, venlafaxine, bupropion, and others. The warning was expanded in 2007 to include young adults up to age 24. It’s not just about suicide attempts. It’s about sudden changes: increased agitation, panic attacks, insomnia, hostility, or impulsivity. These aren’t side effects you can ignore. They’re red flags that need immediate attention. The FDA didn’t say antidepressants cause suicide. They said they can trigger suicidal thinking in vulnerable teens during the early weeks of treatment. And they required every pharmacy to hand out a Patient Medication Guide with every prescription. That guide tells families: Watch closely. Call your doctor if behavior changes.The Unintended Consequences

Here’s where things get complicated. After the warning went live, prescriptions for teens dropped by 22% within two years. Parents got scared. Doctors got nervous. Some stopped prescribing altogether. A 2023 study in Health Affairs looked at 11 high-quality studies tracking what happened after the warning. The results were startling:- Teen visits for depression dropped by 14.5%

- Depression diagnoses fell by 18.7%

- Antidepressant prescriptions fell by 22.3%

- Psychotherapy visits also declined by 11.9%

Is the Risk Real? Or Overstated?

Critics of the warning point out something important: the original data came from short-term clinical trials, not real-world use. In those trials, patients were carefully screened. Most had moderate depression. The 4% risk was based on a small number of events-just 66 out of 4,400 kids. Many of those “suicidal thoughts” were mild, temporary, and resolved with dose adjustments or extra support. A 2023 Cochrane review of 34 randomized trials found the evidence for suicidality risk was “low to very low” due to poor study design and tiny event numbers. Meanwhile, other studies show antidepressants reduce suicide risk in the long term. A 2022 Mayo Clinic survey of 1,200 teens on SSRIs found 87% improved without any suicidal thoughts. Only 3% had transient suicidal ideation-and it went away after their dose was tweaked or they got more therapy. The American Psychiatric Association and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry now agree: for teens with moderate to severe depression, the benefits of antidepressants outweigh the risks. But the warning hasn’t changed. It’s still there. And it’s still scaring people.What Monitoring Actually Looks Like

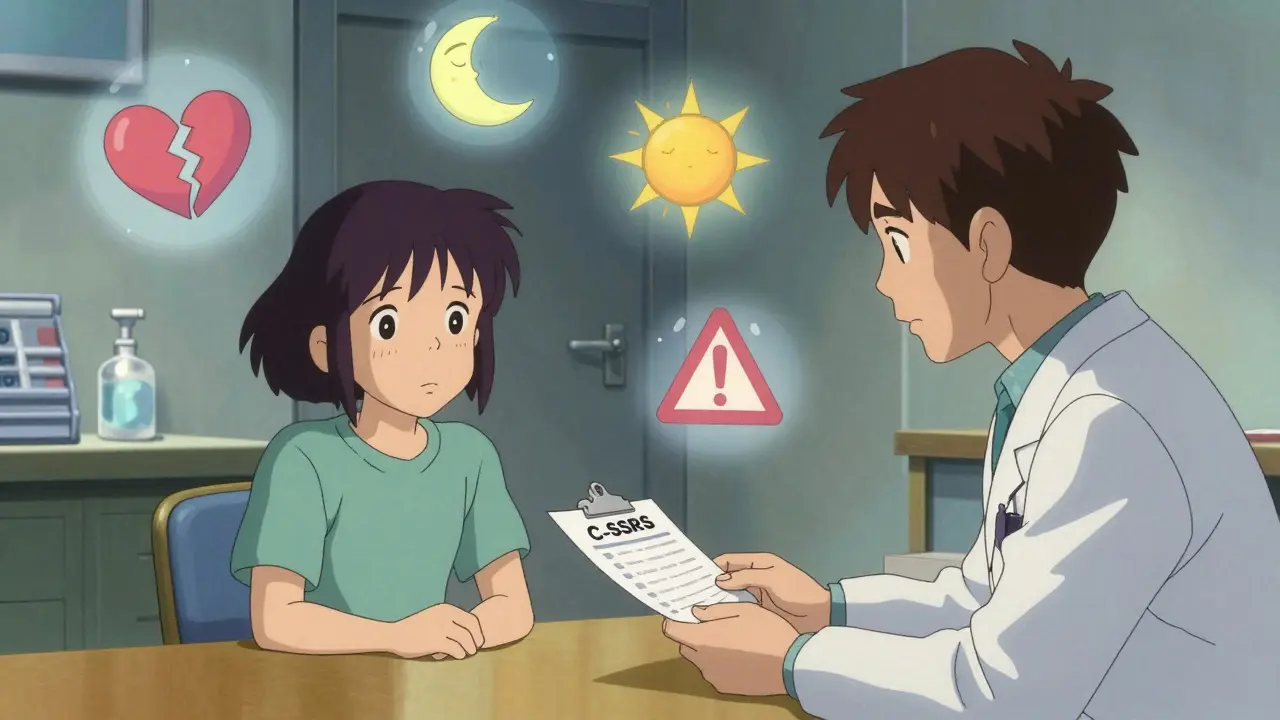

The FDA didn’t just slap on a warning and walk away. They expected doctors to step up. But here’s the catch: a 2021 survey of 500 child psychiatrists found that no study showed an increase in monitoring after the warning. Instead, doctors spent more time explaining the warning to worried parents-and that delayed treatment by an average of 3.2 weeks. Real monitoring isn’t a checkbox. It’s active, consistent, and personalized:- Week 1: In-person or telehealth visit. Ask: “Have you had thoughts about not wanting to live?” Use the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). Check sleep, energy, appetite, and mood.

- Week 2: Follow-up. Look for agitation, restlessness, or withdrawal. Parents should report any sudden changes.

- Week 4: Full assessment. Has the teen’s mood improved? Are they talking more? Sleeping better? If not, consider dose adjustment or adding therapy.

- Month 2-3: Biweekly check-ins. Keep using the C-SSRS. Talk to school counselors if possible.

- After 3 months: Monthly visits, unless something changes.

What Families Should Do

If your teen is being considered for an antidepressant:- Ask your doctor: “What specific signs should I watch for in the first 6 weeks?”

- Request the FDA’s Patient Medication Guide. Read it together.

- Don’t skip therapy. Antidepressants work best with counseling-especially CBT.

- Keep all appointments. Even if your teen feels fine, don’t cancel the follow-ups.

- Remove access to pills, firearms, and other lethal means. This is critical.

- Know that if suicidal thoughts appear, it doesn’t mean the drug is “wrong.” It means you need to adjust.

What’s Changing? What’s Next?

More than 20 years after the first antidepressants were prescribed for teens, the evidence is shifting. The FDA’s own advisory committee met in September 2024 to review the data. Experts from the APA, AACAP, and leading research institutions are calling for the black box warning to be replaced with a standard warning-clear, but not paralyzing. The goal isn’t to downplay risk. It’s to balance it. Depression kills. Untreated depression kills faster than any drug ever could. The black box warning was meant to save lives. But the data now suggests it may have cost them. The message today is simple: Don’t avoid treatment out of fear. Use treatment wisely. With careful monitoring, antidepressants are one of the most effective tools we have for helping teens come back from the edge.Do antidepressants cause suicide in teens?

No, antidepressants do not cause suicide. But they can increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviors in some teens during the first few weeks of treatment. This is why close monitoring is required. Depression itself is the leading cause of suicide in adolescents. The goal of treatment is to reduce that risk by improving mood and function.

Which antidepressants are safest for teens?

Fluoxetine (Prozac) is the only antidepressant approved by the FDA for treating depression in children 8 and older. Sertraline (Zoloft) is also widely used and well-studied in teens. Both are SSRIs. While all antidepressants carry the black box warning, fluoxetine has the strongest evidence for benefit in adolescents. Other medications like bupropion or mirtazapine may be used off-label, but with less data.

How long should a teen stay on antidepressants?

Most clinicians recommend staying on the medication for at least 6 to 12 months after symptoms improve. Stopping too soon increases the risk of relapse. If the teen responds well and has strong support systems (therapy, family, school), the doctor may slowly taper the dose. Never stop abruptly-this can cause withdrawal symptoms or return of depression.

What if my teen refuses to take the medication?

Refusal is common, especially if they’ve heard about the black box warning. Talk to them without judgment. Ask what they’re afraid of. Consider starting with therapy alone. If depression is severe, involve a therapist who specializes in motivational interviewing. Sometimes, a short trial-say, 4 weeks-with weekly check-ins helps teens see the benefits themselves. Never force medication, but don’t let fear prevent treatment either.

Are there alternatives to antidepressants for teens?

Yes. For mild to moderate depression, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is just as effective as medication-and has no side effects. Exercise, sleep hygiene, and family therapy also help. But for severe depression-with suicidal thoughts, inability to get out of bed, or failing school-medication is often necessary. Therapy alone may not be enough. The best results come from combining both.