Folic Acid vs. Methylfolate vs. Folinic Acid Decision Guide

This tool helps you choose the most suitable folate supplement based on your health profile and goals. Answer the following questions to get personalized recommendations.

Your Personalized Recommendation

Quick Summary / Key Takeaways

- Folic Acid is a synthetic, inexpensive form of vitamin B9 that needs conversion in the body.

- Methylfolate (5‑MTHF) is the active, ready‑to‑use form and works best for people with MTHFR gene variants.

- Folinic Acid (Leucovorin) bypasses most conversion steps and is useful in clinical settings or high‑dose therapy.

- Food‑derived folate offers the highest natural bioavailability but is harder to standardize in supplements.

- Choose based on health goal, genetic background, and tolerance; pregnant people often stick with folic acid unless a doctor advises otherwise.

What Is Folic Acid?

Folic Acid is a synthetic form of vitamin B9 that was first added to grain products in the 1990s to reduce neural‑tube defects. Chemically it is a stable, white powder that survives heat and storage, which makes it cheap and easy to include in tablets, powders, and fortified foods. Once ingested, the liver converts it into dihydrofolate and then into tetrahydrofolate, the active carrier used in DNA synthesis and amino‑acid metabolism.

Typical adult dosing ranges from 400µg (the amount most multivitamins provide) up to 5mg when prescribed for specific medical conditions. Because the conversion relies on several enzymes, the efficiency varies widely among individuals.

Common Alternatives to Folic Acid

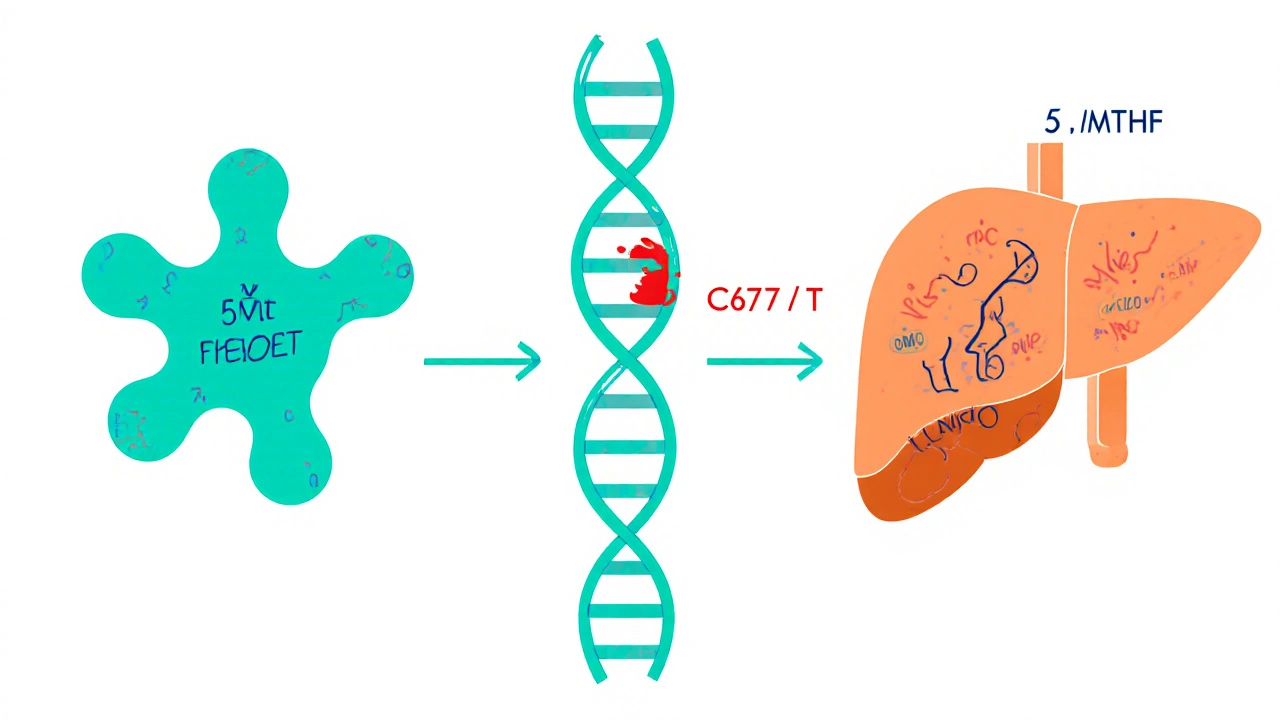

Methylfolate (5‑MTHF) is the form that the body ultimately uses. It arrives already methylated, so the liver’s conversion steps are largely skipped. This makes it the go‑to choice for people with a sluggish MTHFR enzyme, a genetic variant that hampers the conversion of folic acid to its active state.

Folinic Acid (Leucovorin) sits one step before the final active form. It can be turned into tetrahydrofolate without needing the dihydrofolate reductase step that folic acid requires. Clinicians often prescribe folinic acid to mitigate the side‑effects of certain chemotherapy drugs or to treat folate‑deficiency anemia.

When talk turns to natural sources, Folate refers to the collection of naturally occurring B9 compounds found in leafy greens, legumes, and citrus. These molecules are already in a reduced state, giving them the highest intrinsic bioavailability, but the amount you get from a single supplement is limited.

In the broader supplement market, Prenatal Vitamin formulas often combine folic acid (or sometimes methylfolate) with iron, calcium, vitamin B12, and other nutrients essential for a growing baby. The inclusion of Vitamin B12 is critical because both B9 and B12 work together to keep homocysteine levels in check, a marker linked to cardiovascular risk.

How the Forms Differ - Bioavailability, Activation, Safety

Bioavailability measures how much of the ingested nutrient actually reaches the bloodstream in its active form. Folate from foods scores the highest (about 80‑100%); methylfolate follows closely (about 70‑80%); folinic acid sits around 60‑70%; and folic acid lags behind (40‑60%), especially in people with MTHFR variants.

Activation pathway is another key factor. Folic Acid → Dihydrofolate → Tetrahydrofolate (requires three enzymes). Methylfolate skips straight to the methylated tetrahydrofolate, needing only a single transport step. Folinic Acid bypasses the dihydrofolate stage, making it a middle‑ground option.

Safety profile should not be overlooked. High doses of folic acid (above 1mg daily) can mask vitamin B12 deficiency, potentially leading to nerve damage if B12 isn’t supplemented. Methylfolate, being already active, does not mask B12 deficiency but can cause mild flushing in sensitive individuals. Folinic acid is considered safe even at therapeutic doses, as it doesn’t accumulate unmetabolized folic acid in the bloodstream.

When to Choose Which Form

Pregnancy: Most obstetric guidelines still recommend 400‑800µg of folic acid daily for early pregnancy because the evidence base is strongest. However, women who know they carry the MTHFR C677T mutation may benefit from a methylfolate‑based prenatal vitamin, provided their doctor agrees.

Genetic considerations: If you’ve had a genetic test that shows reduced MTHFR activity, switching to methylfolate can improve homocysteine clearance and reduce fatigue. Many labs now report the C677T and A1298C polymorphisms, which together explain why some people feel “no effect” from standard folic acid supplements.

Medical therapy: Patients undergoing methotrexate treatment for rheumatoid arthritis or certain cancers often receive folinic acid rescue doses to protect healthy cells. In this setting, folinic acid’s ability to bypass the enzyme blocked by methotrexate is a lifesaver.

General health & longevity: For adults without specific risk factors, a low‑dose folic acid (400µg) in a multivitamin is usually sufficient. If you’re interested in supporting methylation pathways for mood or cognitive function, a modest methylfolate supplement (400‑800µg) may be more effective.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison

| Attribute | Folic Acid | Methylfolate (5‑MTHF) | Folinic Acid (Leucovorin) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical class | Synthetic p‑aminobenzoic acid derivative | Natural methylated tetrahydrofolate | 5‑Formyl tetrahydrofolate (reduced) |

| Bioavailability* | 40‑60% | 70‑80% | 60‑70% |

| Typical dose (adult) | 400µg - 5mg (prescribed) | 400µg - 1mg (OTC) | 400µg - 5mg (clinical) |

| Conversion steps needed | 3 enzymatic steps | 0 (already active) | 1‑2 steps |

| Best for | General population, pregnancy (per guidelines) | MTHFR variants, methylation support | Methotrexate rescue, high‑dose therapy |

| Potential drawback | Unmetabolized folic acid can build up | May cause mild flushing | More expensive, less common |

*Bioavailability figures are averages from peer‑reviewed nutrition studies published between 2018‑2023.

Practical Tips & Common Pitfalls

- Check label wording: “folic acid” vs. “methylfolate” - the latter will often be listed as “5‑MTHF” or “L‑5‑MTHF”.

- If you’re on medication that interferes with folate metabolism (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin), talk to your pharmacist about using folinic acid instead of folic acid.

- Never exceed the recommended prenatal dose without medical supervision; excess folic acid can hide a B12 deficiency.

- Store supplements in a cool, dry place. Heat and humidity can degrade folate compounds faster than many vitamins.

- Consider a blood test for homocysteine or a genetic test for MTHFR if you’re unsure which form is right for you.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take both folic acid and methylfolate together?

Mixing the two isn’t harmful, but it’s usually unnecessary. If you’ve already chosen methylfolate for its higher bioavailability, adding folic acid won’t boost results and could increase the chance of unmetabolized folic acid in the blood.

Why do some prenatal vitamins use methylfolate instead of folic acid?

Manufacturers target women who have the MTHFR gene variant or who prefer a single‑step active form. Studies show that methylfolate can reduce blood homocysteine faster, which is a benefit during early fetal development.

Is folinic acid safe for daily supplementation?

Folinic acid is safe at therapeutic doses under medical supervision. For routine daily use, most experts still recommend the cheaper folic acid unless you have a specific medical indication.

How can I know if I have an MTHFR variant?

A simple saliva or blood DNA test from a certified lab can report the C677T and A1298C polymorphisms. Many nutrition clinics offer this as part of a broader micronutrient panel.

Does cooking destroy folate in foods?

Yes, folate is water‑soluble and heat‑sensitive. Steaming vegetables for a short time retains more folate than boiling, which can leach the vitamin into the cooking water.

Next Steps & Troubleshooting

If you’ve decided that methylfolate is the right fit, start with a 400µg daily tablet and monitor how you feel after a week. If you notice any flushing or mild headache, reduce the dose to 200µg and increase gradually.

For anyone experiencing persistent fatigue despite supplementation, consider checking homocysteine levels and B12 status. A high homocysteine reading often signals a need for more active folate or additional B12.

Finally, remember that supplements support-not replace-a balanced diet. Aim for folate‑rich foods like spinach, lentils, and oranges, and use the supplement to fill any gaps identified by your health professional.

If you’re looking for the most bioavailable option, methylfolate is often recommended, but the best choice always depends on your unique health profile and physician guidance.