When a blockbuster drug’s core patent expires, you’d expect generics to flood the market. But in many cases, they don’t. Why? Because the brand company already filed a formulation patent on a combination of the same drugs-just packaged differently. These aren’t new medicines. They’re the same active ingredients, sometimes in slightly altered ratios, delivered via a new device, or dosed at a different frequency. And yet, they can block generics for years longer than the original patent allowed.

What Exactly Is a Formulation Patent on a Drug Combination?

A formulation patent doesn’t protect the chemical structure of a drug. That’s the job of a composition-of-matter patent, which usually expires first. Instead, a formulation patent covers how the drug is put together: the exact ratio of ingredients, the type of capsule or tablet, the release speed, the delivery method, or even the way it’s administered. For example, instead of two separate pills, a company might combine two drugs into a single tablet. Or they might switch from an IV infusion to a subcutaneous injection that patients can give themselves at home. These aren’t always major clinical breakthroughs. But if they can prove the new version works better-faster, safer, more consistently-they can get a new patent. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) recorded over 1,800 formulation patent applications in 2022 alone. Most of these were for drugs already on the market. And 78% of new drug approvals between 2015 and 2020 included at least one of these secondary patents, according to the Journal of Managed Care & Pharmacy.How These Patents Block Generic Entry

Generic manufacturers can’t just copy the original drug and sell it. If a brand company holds a valid formulation patent on a combination, the generic must either:- Wait until the formulation patent expires

- Design around it by changing the ratio, delivery method, or excipients

- Only market the drug for uses not covered by the patent

Why the Patent Office Grants Them (Sometimes)

You’d think combining two known drugs is obvious. And under the 2007 KSR v. Teleflex Supreme Court ruling, that’s exactly what patent examiners are supposed to assume. If two drugs are already used for the same condition, combining them shouldn’t be patentable-unless you can prove something unexpected happened. That’s the hurdle. To get approved, a formulation patent must show:- Statistically significant improvement in efficacy or safety

- A novel delivery mechanism that changes how the drug behaves

- An exact ratio that produces results not seen in prior combinations

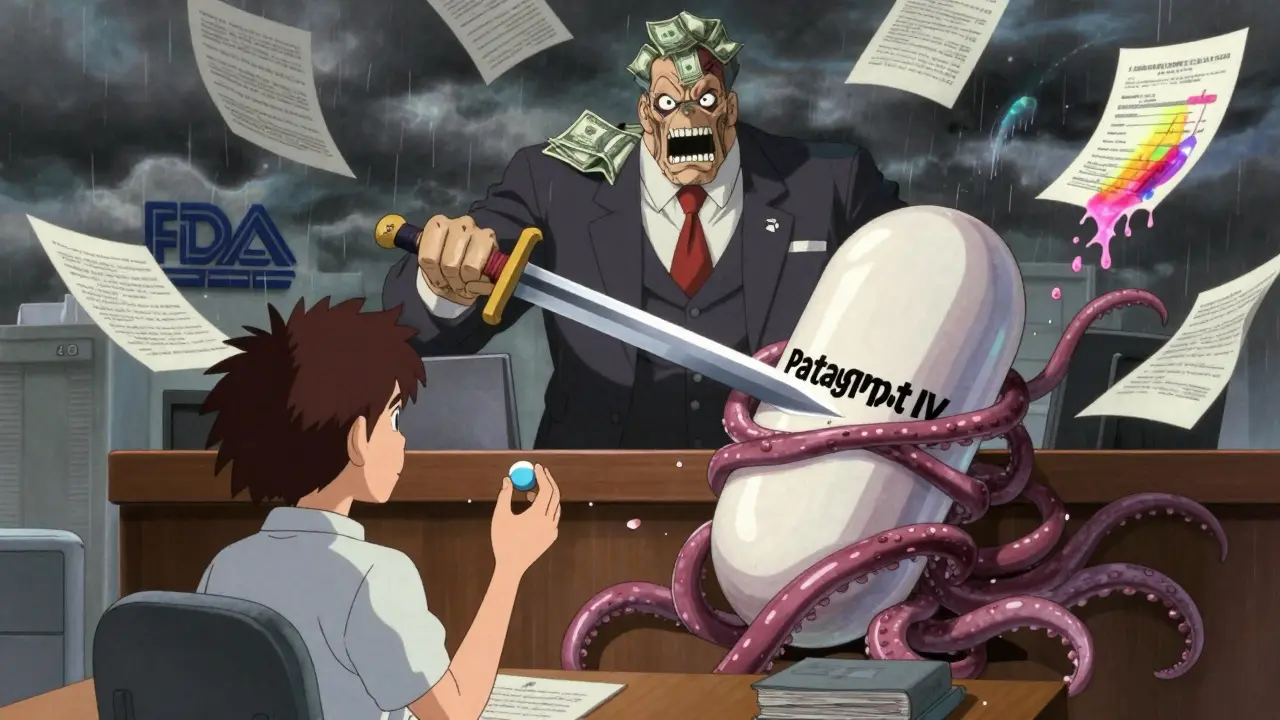

The Dark Side: Evergreening and Product Hopping

Not all formulation patents are created equal. Some are borderline scams. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) calls it “product hopping.” That’s when a company stops making the original version of a drug and pushes patients to a new patented version-even if the change offers little or no real benefit. They might switch from a tablet to a capsule, or add a sugar coating. No clinical improvement. Just a new patent. The FTC has 17 active investigations into this practice as of September 2024. One notorious case involved oxaliplatin, where the brand discontinued the original formulation and forced doctors to switch to a new patented version. Patients didn’t get better outcomes. But the company kept its monopoly. A 2022 JAMA Internal Medicine study found that 31% of combination patents between 2015 and 2022 covered trivial changes like salt forms or excipient tweaks-with no evidence of improved patient outcomes. Harvard’s Dr. Aaron Kesselheim called it “patent privateering”-using the system to extract profits without advancing care.Who Wins and Who Loses?

The winners? Big pharma. Top 10 companies average 14.7 formulation patents per blockbuster drug. Mid-sized firms? Only 3.2. The difference? Resources. Only the giants can afford the $28-42 million in extra R&D needed to prove unexpected results. The losers? Patients and payers. The Congressional Research Service estimates that secondary patents raise U.S. drug prices by 17-23% beyond what innovation justifies. In 2023, formulation and combination patents protected $312 billion in global drug sales-22% of the entire pharmaceutical patent market. But the tide is turning. Generic manufacturers filed 842 Paragraph IV challenges in 2023-up from 517 in 2020. Courts are applying stricter obviousness standards. And 45% of formulation patents are now being invalidated in litigation.What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond?

Regulators are pushing back. In May 2024, the FDA proposed requiring “clinical superiority” evidence for any new formulation seeking 3-year exclusivity. That’s a big deal. It means no more patenting minor tweaks. Congress is also considering the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act. If passed, it would limit secondary patents to those that demonstrate “meaningful clinical benefit.” That could invalidate nearly 28% of current formulation patents, according to CRS modeling. Meanwhile, companies are adapting. Roche’s 2023 patent for a trastuzumab-deruxtecan combination with pH-sensitive release technology isn’t just a tweak-it’s a new delivery mechanism that requires 2.3 years of extra development. That’s the future: real innovation, not just legal maneuvering.

How Long Does This Strategy Last?

On average, formulation patents add 3-8 years of exclusivity beyond the original patent. Some drugs, like Eli Lilly’s Humalog insulin, have extended exclusivity for up to 16 years. Others, with weak portfolios, only get 3 extra years. But the trend is clear: the average extension is shrinking. From 5.3 years (2020-2023), it’s projected to drop to 3.8 years (2025-2030). Why? Because generics are getting smarter. Courts are getting stricter. And regulators are no longer turning a blind eye.What Does This Mean for Patients?

If you’re taking a combination drug, you might be on a version that’s been tweaked to keep the brand in control. You might not know it. But if your prescription suddenly switches from a pill to an injection, or from one brand to another with the same ingredients, it’s likely not because your doctor chose it-it’s because the original is off-patent, and the new version isn’t. The good news? More generic alternatives are coming. The bad news? It’s taking longer. And some of those delays are based on patents that don’t make you healthier-just richer.Can a generic drug copy a combination product if the original patent expired?

No, not if a formulation patent is still active. Even if the core patent on the individual drugs expired, a newer patent covering their specific combination, ratio, or delivery method can block generics. The generic manufacturer must either wait for that patent to expire, design a non-infringing version, or challenge it in court through a Paragraph IV certification.

What’s the difference between a composition-of-matter patent and a formulation patent?

A composition-of-matter patent protects the chemical structure of a single active ingredient-it’s the strongest and earliest patent. A formulation patent protects how multiple ingredients are combined, delivered, or dosed. It doesn’t protect the chemicals themselves, just their arrangement. Formulation patents are weaker legally but strategically vital for extending market control after the main patent expires.

Why do some formulation patents get rejected by the USPTO?

Most rejections happen because the combination is deemed “obvious” under KSR v. Teleflex. If two drugs are already used together in practice, or if the ratio or delivery method is a routine tweak, the patent office will reject it. Other common reasons include insufficient clinical data, lack of unexpected results, or poor claim drafting-like using vague language instead of precise measurements.

How do companies prove their combination is not obvious?

They run head-to-head clinical trials showing statistically significant improvements-like better response rates, fewer side effects, or easier administration. The data must be strong: p-values under 0.01, large sample sizes, and direct comparison to existing treatments. Even small improvements, like reducing injection time from 15 minutes to 2 minutes, can count if they’re proven to improve patient adherence.

Are formulation patents legal?

Yes, they’re legal-and they’re granted every day. But their legitimacy is under heavy scrutiny. While some represent real innovation, others are seen as legal loopholes to delay competition. Regulators like the FTC and FDA are tightening rules, and courts are increasingly invalidating patents that lack true clinical benefit. The line between innovation and exploitation is getting thinner.

What therapeutic areas use formulation patents the most?

Oncology leads the way, with 78% approval rates for formulation patents due to complex delivery needs and high patient willingness to accept new methods. Immunology and rare diseases follow closely. In contrast, CNS drugs have much lower approval rates (43%) because combining neurological agents is often seen as obvious. Biologics, especially, benefit from formulation patents because delivery systems (like auto-injectors) are highly patentable.