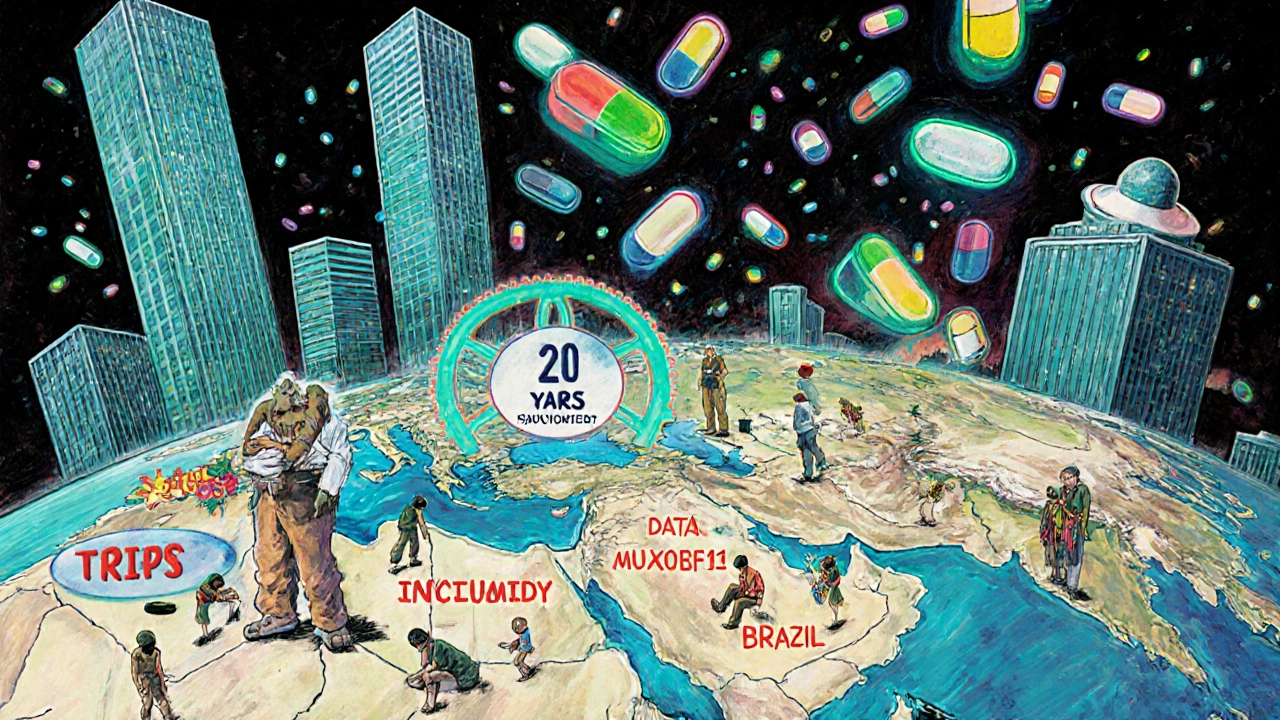

When you need a life-saving drug, the price shouldn’t depend on where you live. But for millions in low- and middle-income countries, it does. The reason lies in a 30-year-old international trade deal called the TRIPS Agreement - and how it changed the rules for generic medicines forever.

What the TRIPS Agreement Actually Does

The TRIPS Agreement, short for Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, is a global rulebook created by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. It forced 164 countries - including poor nations - to adopt strict patent laws that didn’t exist before. Before TRIPS, only 23 of 102 developing countries allowed patents on medicines. Now, nearly all do.Here’s the core change: TRIPS requires every country to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceutical products, starting from the date the patent is filed. That means a drug company can stop anyone else from making or selling the same medicine, even if it’s chemically identical. Before TRIPS, countries like India and Brazil could make cheaper versions using different manufacturing methods. After TRIPS, that became illegal.

The goal, according to pharmaceutical companies and wealthy nations, was to encourage innovation. They argue that without strong patents, no one would spend billions developing new drugs. But the cost? Millions of people losing access to affordable treatments for HIV, cancer, hepatitis, and tuberculosis.

How Generic Drugs Got Blocked

Generic drugs are copies of brand-name medicines. They work the same way, but cost 80-95% less. In the 1990s, India was the pharmacy of the developing world, producing low-cost antiretrovirals for HIV. After TRIPS, India had to change its laws by 2005. The result? Prices for cancer drugs like imatinib jumped 300-500% overnight.But patents aren’t the only barrier. TRIPS also introduced something called “data exclusivity.” Even after a patent expires, regulatory agencies can’t use the original drug maker’s clinical trial data to approve a generic version. That means generic companies must run their own expensive, time-consuming trials - something most can’t afford. In many countries, this adds 5-10 extra years of monopoly.

Then there’s “patent linkage.” Some countries, pressured by the U.S. and EU through trade deals, now require drug regulators to check for active patents before approving any generic. This creates legal delays, even when patents are weak or expired. According to the Access to Medicine Foundation, 65% of low-income countries now face these extra hurdles.

The Compulsory License Loophole (That Almost Didn’t Work)

TRIPS isn’t completely rigid. Article 31 lets governments issue “compulsory licenses” - allowing local companies to make generic versions without the patent holder’s permission, if it’s for public health. This was meant to be a safety valve.But there was a catch. Paragraph (f) said these licenses had to be used “predominantly for the domestic market.” That meant countries without drug factories - like Rwanda or Botswana - couldn’t import generics made elsewhere. Even if they had the money, they had no way to get the medicine.

In 2001, the Doha Declaration tried to fix this. It said public health emergencies override patent rights. But the real fix came in 2007: a legal amendment allowing countries to export generics made under compulsory license. Sounds good, right? In practice, it was a nightmare. The paperwork was complex. Few countries had the legal or administrative capacity to use it. By 2016, only one shipment of malaria medicine had ever moved under this rule.

Canada and Rwanda were the only two countries to ever make it work - and even then, it took years of legal battles. The system was designed to fail.

Who Won? Who Lost?

The winners are clear: big pharmaceutical companies. Between 2010 and 2020, 70% of new drugs came from firms based in countries with strong patent systems - the U.S., EU, Japan. These companies now earn billions from monopoly pricing.The losers? Patients in poor countries. Before generics, HIV treatment cost $10,000 per person per year. Today, thanks to generic competition in places like India and Brazil, it’s down to $75. But that’s only for older drugs. Newer treatments - for hepatitis C, cancer, or rare diseases - still cost $300-$600 per year, even in generics. Why? Because they’re still under patent.

And it’s getting worse. Countries are now signing “TRIPS Plus” deals - bilateral trade agreements that demand even stricter rules than the WTO requires. The EU-Vietnam deal, for example, gives 8 years of data exclusivity, far beyond TRIPS. The U.S. has included patent term extensions in 85% of its free trade agreements.

Meanwhile, the World Health Organization found that between 1975 and 1997, only 13 of 1,223 new drugs developed were for tropical diseases - diseases that mostly affect poor countries. Innovation isn’t being directed where it’s needed most.

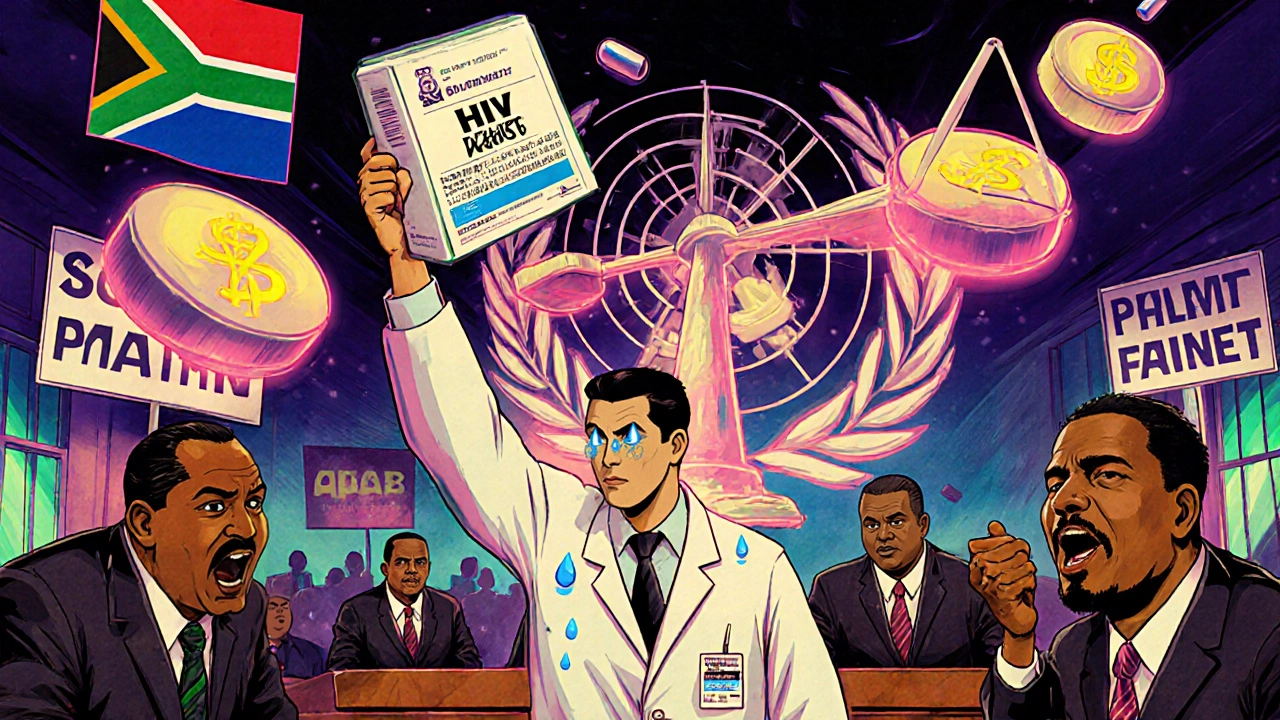

Real-World Battles: Brazil, South Africa, India

Brazil tried to produce its own generic HIV drugs in 2000. The U.S. threatened trade sanctions under Section 301. Brazil stood firm. The U.S. backed down.South Africa passed a law in 1998 to allow generic imports. Forty pharmaceutical companies sued them - including Pfizer and Merck. The case made global headlines. After protests from activists, NGOs, and the UN, the companies dropped the lawsuit in 2001.

India’s transition to product patents in 2005 was messy. The country had to stop making cheap versions of drugs like imatinib, used to treat leukemia. Prices soared. A 2008 Lancet study found the cost of cancer drugs jumped 300-500%. But India didn’t give up. It used legal loopholes - like rejecting weak patents - to keep generics alive. Today, it still produces 60% of the world’s generic medicines.

The COVID-19 Wake-Up Call

When the pandemic hit in 2020, the world saw what TRIPS really meant. Vaccine makers held patents on mRNA technology. Countries like India and South Africa asked the WTO to temporarily waive patent rights for vaccines and treatments. Over 100 nations supported it.The U.S., EU, and Switzerland blocked it for over a year. When they finally agreed to a partial waiver in June 2022, it was too late for most. The waiver only applied to vaccines, not treatments. It had complex conditions. No country has used it yet.

It proved one thing: when profits are at stake, global health takes a back seat.

Is There a Way Forward?

The Medicines Patent Pool, created in 2010, is one of the few working solutions. It negotiates voluntary licenses with drug companies so generics can be made and sold in low-income countries. So far, it’s helped 17.4 million people get HIV, hepatitis C, and TB drugs.But voluntary deals aren’t enough. They depend on the goodwill of corporations. And they don’t cover new drugs fast enough.

What’s needed? Stronger use of compulsory licensing. Removing data exclusivity. Banning patent linkage. And stopping “TRIPS Plus” clauses in trade deals.

Some countries are trying. Thailand has issued compulsory licenses for heart and cancer drugs. Brazil still produces generics for HIV. Kenya and Malaysia are building regulatory capacity to approve generics faster.

But without global pressure, the system won’t change. The TRIPS Agreement wasn’t designed to save lives. It was designed to protect profits. And until that changes, millions will keep dying because the medicine they need is too expensive.

What is the TRIPS Agreement and why does it matter for generic drugs?

The TRIPS Agreement is a global rule under the WTO that requires all member countries to grant 20-year patents on pharmaceutical products. Before TRIPS, many developing countries could make generic versions of drugs using different manufacturing methods. TRIPS ended that flexibility, forcing countries to honor product patents. This directly limits the production and import of low-cost generics, raising drug prices and reducing access.

Can countries still make generic drugs under TRIPS?

Yes, but it’s hard. TRIPS allows compulsory licensing - where a government lets a local company produce a generic version without the patent holder’s permission - if it’s for public health. But there are strict conditions: the license must be non-exclusive, mostly for domestic use, and the country must first try to negotiate with the patent holder. Exporting generics made under license was nearly impossible until 2007, and even now, the process is so complex that only a few shipments have ever happened.

What is data exclusivity and how does it block generics?

Data exclusivity means that even after a drug’s patent expires, regulatory agencies can’t use the original company’s clinical trial data to approve a generic version. Generic makers must run their own expensive and time-consuming trials. This adds 5-10 years of extra monopoly time beyond the patent. In many countries, this is the real barrier to generics - not the patent itself.

Why do rich countries push for TRIPS Plus rules?

Rich countries, especially the U.S. and EU, use bilateral trade deals to demand even stronger patent rules than TRIPS requires. These include longer patent terms, extended data exclusivity, and restrictions on compulsory licensing. Their goal is to protect pharmaceutical profits and delay generic competition. But for low-income countries, these rules mean higher drug prices and fewer treatment options.

Has the TRIPS Agreement improved global health?

Not for most people in poor countries. While it may have boosted R&D in wealthy nations, TRIPS has delayed generic access by 10-15 years in developing regions. The World Health Organization found that patented drugs cost 200-300% more after TRIPS. New medicines for tropical diseases - which affect millions - are rarely developed. The only real progress came from countries like India and Brazil that fought back with compulsory licenses and local production - not from the TRIPS system itself.

What can be done to fix the system?

Countries need to fully use TRIPS flexibilities: issue compulsory licenses without delay, eliminate data exclusivity, ban patent linkage, and reject TRIPS Plus clauses in trade deals. Global pressure is needed to stop wealthy nations from forcing stricter rules on poorer ones. The Medicines Patent Pool shows voluntary deals can work - but they’re not enough. Real change requires legal reform, political will, and public advocacy.

Every day, someone dies because they can’t afford a medicine that exists. The problem isn’t science - it’s policy. And policy can be changed.