MS Vertigo Symptom Checker

Answer the following questions to assess whether your vertigo may be related to Multiple Sclerosis:

Below is a comparison between central (MS-related) and peripheral vertigo:

| Feature | MS-Related (Central) Vertigo | Peripheral Vertigo (e.g., BPPV) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Trigger | Often spontaneous; may worsen with fatigue or heat | Head position changes, especially rolling over |

| Nystagmus Direction | Direction changes with gaze; vertical or torsional components | Horizontal-rotatory, remains consistent |

| Associated Neurological Signs | Double vision, limb weakness, sensory disturbances | Usually isolated to balance; hearing loss only in vestibular neuritis |

| Imaging Findings | MRI shows lesions in brainstem, cerebellum, or cortical vestibular area | Normal MRI; CT may show inner-ear inflammation |

| Response to Repositioning Maneuvers | Limited or none | Often dramatic improvement (e.g., Epley maneuver) |

Feeling like the room is spinning can be terrifying, especially when it pops up out of nowhere. For people living with vertigo and multiple sclerosis, that dizzy episode might be more than just a fleeting nuisance-it could be a clue about how the disease is affecting the brain’s balance system. This guide breaks down why vertigo shows up in MS, how doctors tell it apart from other causes, and what you can do to feel steadier.

What Is Vertigo?

Vertigo is a sensation that either you or your surroundings are moving when they’re actually still. It differs from simple light‑headedness because the feeling is rotational and often comes with nausea, imbalance, or eye movements called nystagmus. The sensation can arise from problems in the inner ear (peripheral vertigo) or from the brain’s vestibular pathways (central vertigo).

What Is Multiple Sclerosis?

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease where the body attacks the protective myelin sheath around nerve fibers in the central nervous system. This demyelination slows or blocks nerve signals, leading to a wide range of symptoms-from fatigue and vision loss to muscle weakness and coordination problems. MS is unpredictable; lesions can appear anywhere in the brain or spinal cord, which is why symptoms can seem unrelated.

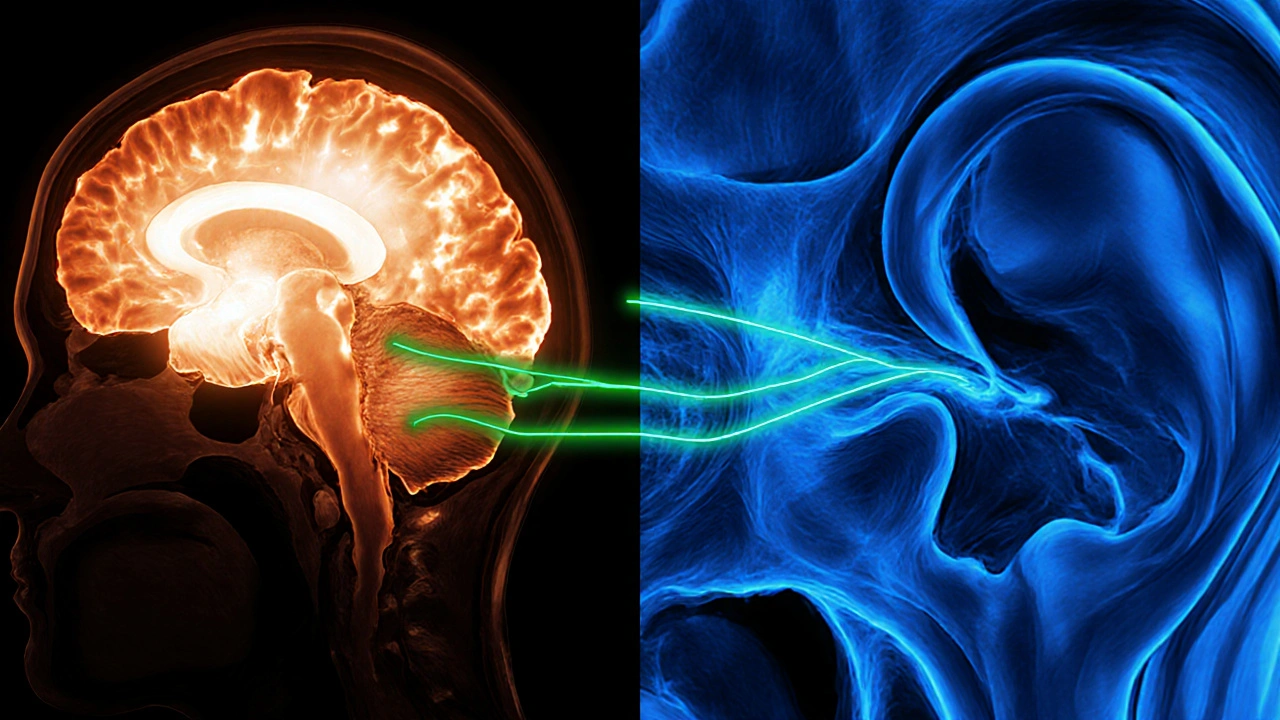

Why Vertigo Happens in MS

When MS lesions involve the vestibular network, the brain can’t process balance information correctly. The most common spots are:

- Brainstem, which houses the vestibular nuclei that coordinate eye and head movements.

- Cerebellum, the coordination center that fine‑tunes balance.

- Vestibular pathways that run through the thalamus and cortical vestibular area.

A lesion in any of these areas can produce central vertigo, which often feels different from ear‑related vertigo. Central vertigo tends to be less intense, may not be triggered by head position, and is often accompanied by other neurological signs such as double vision or weakness.

How Doctors Differentiate MS‑Related Vertigo from Other Types

Because vertigo has many causes, clinicians follow a systematic approach:

- History and Symptom Pattern: They ask whether the spinning worsens with head movement (suggesting peripheral causes like BPPV) or appears spontaneously with other neurological signs (hinting at central involvement).

- Physical Examination: A bedside vestibular exam checks for nystagmus direction, gait stability, and limb coordination. Central nystagmus often changes direction with gaze, while peripheral nystagmus stays horizontal.

- Imaging: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the gold standard. T2‑weighted and FLAIR sequences reveal hyperintense lesions in the brainstem or cerebellum that correlate with vertigo episodes.

- Specialized Tests: Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP) and video‑head‑impulse testing (vHIT) can pinpoint whether the vestibular apparatus or the central pathways are impaired.

- Consultation: A neurologist experienced in MS collaborates with an otolaryngologist or vestibular physiotherapist to rule out common peripheral disorders like Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV).

Comparing MS‑Related Vertigo with Common Peripheral Vertigo

| Feature | MS‑Related (Central) Vertigo | Peripheral Vertigo (e.g., BPPV, Labyrinthitis) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Trigger | Often spontaneous; may worsen with fatigue or heat | Head position changes, especially rolling over |

| Nystagmus Direction | Direction changes with gaze; vertical or torsional components | Horizontal‑rotatory, remains consistent |

| Associated Neurological Signs | Double vision, limb weakness, sensory disturbances | Usually isolated to balance; hearing loss only in vestibular neuritis |

| Imaging Findings | MRI shows lesions in brainstem, cerebellum, or cortical vestibular area | Normal MRI; CT may show inner‑ear inflammation |

| Response to Repositioning Maneuvers | Limited or none | Often dramatic improvement (e.g., Epley maneuver) |

Managing Vertigo When You Have MS

Treating vertigo in MS means addressing both the balance problem and the underlying disease activity.

- Disease‑Modifying Therapies (DMTs): Medications such as interferon‑beta, glatiramer acetate, or newer oral agents reduce new lesion formation, which can indirectly lessen vertigo episodes.

- Corticosteroid Courses: Short‑term high‑dose steroids (e.g., methylprednisolone) can shrink active inflammation and often bring rapid relief during an acute vertigo flare linked to a new lesion.

- Vestibular Rehabilitation: Tailored exercises performed with a vestibular physiotherapist improve gaze stability and balance, helping the brain compensate for damaged pathways.

- Medication for Symptom Control: Antiemetics (e.g., ondansetron) or vestibular suppressants (e.g., meclizine) can be used short‑term, but they may worsen overall coordination if overused.

- Lifestyle Adjustments: Staying hydrated, avoiding rapid temperature changes, and using assistive devices (like a cane) during flare‑ups reduce fall risk.

It’s critical to work with a multidisciplinary team-neurologist, otolaryngologist, physiotherapist, and sometimes occupational therapist-to create a plan that tackles both the disease and the balance issues.

Key Takeaways

- Vertigo can be a direct result of MS lesions in the brainstem, cerebellum, or other vestibular pathways.

- Central vertigo differs from peripheral causes in trigger patterns, eye‑movement signs, and associated neurological symptoms.

- MRI is essential for confirming MS‑related lesions; bedside exams and specialized vestibular tests help differentiate causes.

- Managing vertigo involves disease‑modifying therapy, short‑term steroids for active inflammation, and targeted vestibular rehabilitation.

- Early medical evaluation is vital-if vertigo appears with new neurological signs, contact a neurologist promptly.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can vertigo be the first symptom of multiple sclerosis?

Yes. While fatigue and visual disturbances are more common first signs, about 10‑15% of people report a vertigo episode as their initial alert that something is wrong in the central nervous system.

How long does MS‑related vertigo usually last?

Duration varies. Some people experience minutes‑to‑hours spells that resolve as inflammation settles, while others may have lingering imbalance for weeks if the lesion causes lasting damage.

Are there any home exercises that help?

Gentle gaze‑stabilization drills and balance tasks on a foam surface can be safe starters, but it’s best to get a personalized program from a vestibular physiotherapist to avoid worsening symptoms.

Should I take over‑the‑counter motion sickness pills?

Occasional use of antihistamines like meclizine can calm nausea, but they may also impair coordination. Use them sparingly and discuss long‑term options with your neurologist.

When should I call emergency services?

If vertigo appears with sudden weakness, vision loss, speech difficulties, or loss of bladder control, treat it as a medical emergency-these signs may indicate a new MS relapse or stroke.